What Actually Is Late-Stage Capitalism?

For the term to have any meaning, we need to agree on a definition.

Late-stage capitalism is sort of the COVID of financial politics: people blame all sorts of problems on it, even as others dispute its very existence. We debate the efficacy of various treatments, while many people deny the legitimacy of those remedies. Nobody seems to be able to agree on what it actually is, or where it comes from, or what we might be able to do about it.

I’m not the guy with the answers. I’m not an economist, or a social theorist. I don’t even have a PhD. What I am is a 40-year-old journalist with basic critical-thinking skills and a nose for bullshit. And my aim here is to zero in on a definition of late-stage capitalism we can all agree on. If we could also agree on some of the causes, and the impact, and what we might be able to do about it, that would be icing on the cake.

Let’s start with a definition. When I hear people (with actual critical-thinking skills) talk about late-stage capitalism, they’re drawing a distinction between capitalism as it was under the Eisenhower administration, versus the phase we’re living in today, in the wake of financial deregulation under the Reagan administration.

We should unpack that definition piece-by-piece, starting with Dwight D. Eisenhower. When he began his presidency in 1953, the United States was riding one of the strongest economic tailwinds in human history. We’d emerged victorious from World War II, and after some economic turbulence related to the Korean War, the U.S. economy boomed with record-breaking employment rates and increasing wages.

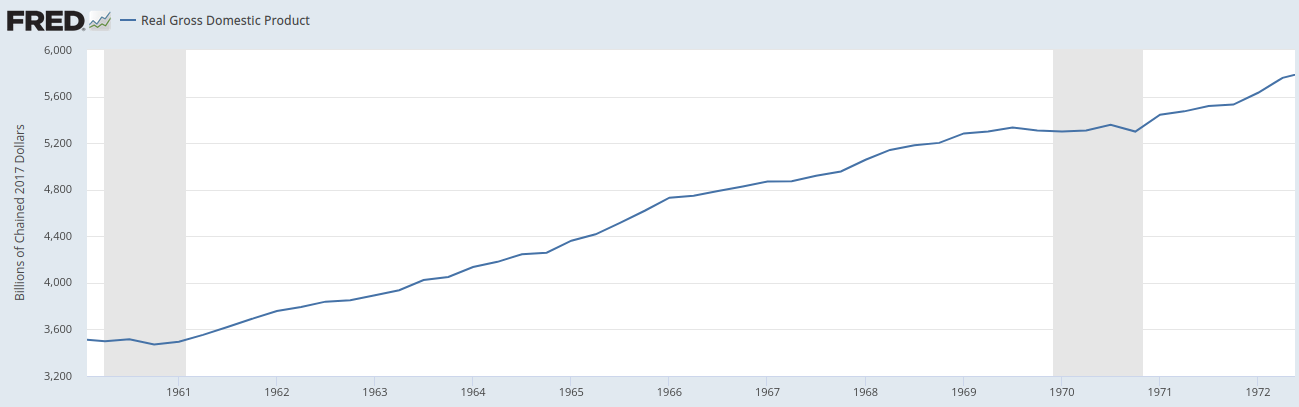

For example, the federal minimum wage was increased from $0.75 per hour to $1.00 per hour on March 1, 1956. Average family income rose from $3,300 in 1950 to $5,600 in 1960. Real gross domestic product (GDP) rose by about 37 percent during that same time period.

However, President Eisenhower recognized that this state of affairs wasn’t sustainable. In his farewell address on January 17, 1961, the President warned against the rising power of the “military-industrial complex,” explaining that “we must guard against unwarranted influence” of a coalition of military groups and industrial corporations who would collude against the people for their own “commercial gain.”

As this video from the National Archives makes clear, Eisenhower was deeply concerned about this looming threat, and insisted on warning the American people of this coming danger to their social and economic future. Take a moment and watch.

But people don’t like to hear bad news. They especially don’t like to hear bad news when they’re enjoying unprecedented economic prosperity, buying new cars at bargain prices, moving to affordable houses in the suburbs to raise the generation who would later become known as the Baby Boomers — named for the socioeconomic boom in which they were born, and whose fruits they enjoyed throughout their lives.

That economic boom continued, despite some fluctuations, into the 1960s. Under President John F. Kennedy’s administration, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 5 percent per year — an increase of more than 55 percent over the course of the decade.

Median family income grew from $5,600 in 1960 to $9,870 in 1970. And not only wages were skyrocketing; purchasing power was increasing, too. The real value of the federal minimum wage peaked in 1968.

This is a crucial point — we’re talking real wages here; that is, wages adjusted for inflation; wages in terms of buying power. This distinction will be very important as we proceed, so let’s keep it in mind.

Because things started to change for the Boomers as the 1960s became the 1970s. Precisely as Eisenhower had warned in 1961, military spending increased by nearly 75 percent between 1965 and 1975.

In fact, as early as January 19, 1969, President Lyndon Johnson revealed that the federal government was running at a $33.5 billion budget deficit. Despite this mountain of national debt, military spending actually increased throughout the 1970s, and has continued to do so ever since. The debt-based economy was born.

Domestically, economic growth slowed in the 1970s. In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) embargoed sales of petroleum to the United States, triggering a 350-percent jump in gas prices, and a corresponding increase in the prices of many consumer goods. America entered a recession. Unemployment rose while buying power plummeted, creating a cycle of stagflation.

Although median family income had risen to $21,020 by the end of the 1970s, it's important to note that this rise in nominal income was accompanied by inflation. For instance, between 1979 and 1980, while the median family income increased by 7.3 percent, a 13.5-percent increase in consumer prices led to a net drop of 5.5 percent in real median family income — that is, a decline in income in terms of buying power.

American families were scared. Their federal government was running at a deficit, their hard-earned money wasn’t stretching as far as it used to, and President Jimmy Carter was no Eisenhower. His responses to the recession and the gas crisis struck many Americans as weak and indecisive. People didn’t want tighter regulations and vague promises. They wanted the American Dream they’d grown up expecting — the prosperity their parents had enjoyed.

So in 1980, when Ronald Reagan campaigned for the presidency on promises of tax cuts and financial deregulation, many Americans’ ears perked up:

Here, it’s very important that we take a close look at what Reagan’s economic policies actually were — what he aimed to achieve, and how he planned to go about doing it. His program of “Reaganomics” included many components, of which the following three were to have the greatest impact on average American families:

Tax cuts. Reagan’s Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA) was the largest tax cut in U.S. history. In particular, ERTA reduced taxes for Americans in the top income bracket from 70 percent to 50 percent. Taxes on American workers in the lowest income bracket, meanwhile, were only reduced from 14 percent to 11 percent. The theory behind this decision is known as Supply-Side Economics (or “Trickle-Down Economics” by its detractors). The basic idea is that tax breaks for corporations and the wealthy will eventually “trickle down” into jobs and wages that benefit everyone. We’ll come back to this in a minute.

Spending cuts. Reagan promised to rein in federal spending, which he did—in some sectors. While military spending significantly increased under Reagan’s two presidential terms, from $267.1 billion in 1980 to $393.1 billion in 1988, he did cut $22 billion from welfare, food-stamp programs, and federal student loans.

Deregulation. Reagan’s administration loosened restrictions across a wide variety of sectors. For example, the The Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 removed the interest rate ceiling for lending institutions, and allowed them to make commercial loans. Reagan’s policies made it made it easier for individuals to borrow money on credit and rack up personal debt. Deregulation also fostered innovation in financial products. For instance, the development and proliferation of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) provided banks with new mechanisms for funding and promoting real estate loans.

All in all, President Reagan did what he’d promised: he cut taxes, deregulated industry, and unleashed a boom in construction and entrepreneurship. As a result, many jobs were created, inflation began to drop, real GDP increased, and purchasing power also saw a short-term rise.

Reaganomics appeared to be working. Small wonder that Reagan got elected to a second presidential term in 1984, announcing that “it’s morning again in America.”

Now let’s take a closer look at the longer-term effects of Reagan’s economic policies, both for average American families and for the United States as a country.

Tax rates. Reagan’s Tax Reform Act of 1986 further lowered the tax rate for top-earning Americans from 50 to 28 percent, while raising the tax rate for low-wage workers to 15 percent.

Income disparity. Unsurprisingly, given these tax policies, the lowest-earning 90 percent of American workers took home a lower share of gross wages in 1989 than they had in 1979.

Capital disparity. A person who makes $250,000 per year (taxed at 28 percent) can live on $180,000 per year much more comfortably than a person who makes $30,000 per year (taxed at 15 percent) can support a family on the remaining $25,500. This disparity in discretionary income leaves low-wage workers with little or no personal savings, while high-income earners can keep adding thousands of dollars more to their savings and investment portfolios, year after year after year. These stockpiles of personal capital then generate their own income in the forms of compound interest and profits from stock sales (capital gains) — at rates of return that (even after taxes) began increasing in the 1950s, and continued to increase throughout the 1970s and 80s.

Purchasing power. Over the course of the 1980s, real wages increased by an average of 41 percent for the top 10 percent of Americans, remained relatively stagnant for the middle class, and declined by about 5 percent for low-wage American workers.

Personal debt. Americans borrowed more from banks throughout the 1980s, and relied increasingly on credit cards.

Mortgage lending. Deregulation in the savings and loan industry led to the Savings and Loan Crisis of the 1980s and early 1990s. Many financial institutions went bust, requiring a government bailout costing over $100 billion, which led to an economic downturn.

National debt. By the end of Reagan’s presidency in 1988, the national debt had increased from $995 billion to $2.9 trillion. Reagan described this as the “greatest disappointment” of his presidency.

Military spending. As mentioned above, military spending significantly increased under Reagan’s two presidential terms, from $267.1 billion in 1980 to $393.1 billion in 1988.

Still, we’ve had a lot of time to correct course since 1989. By now, policymakers have seen Supply-Side Economics crash and burn, and we’ve had five presidential administrations (Republican and Democrat) to undo the damage. And yet, many of these problems remain in force today.

Tax rates: As of 2023, Americans in the top tax bracket pay a tax rate of 37 percent — slightly higher than they paid under Reagan, but still significantly less than the 70-percent tax rate they paid in the 1970s. Americans in the lowest tax bracket pay a 10-percent rate: lower than in the 1970s, which is an improvement — but still high enough to make upward economic mobility very difficult.

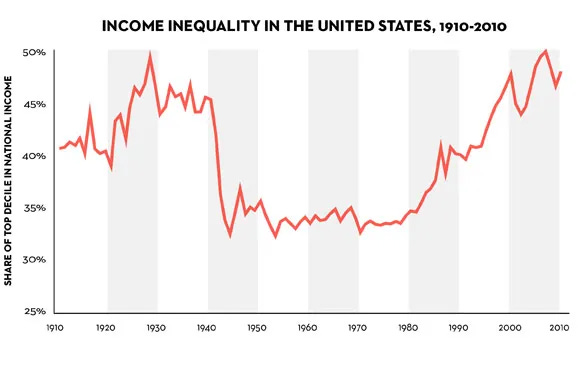

Income disparity: And indeed, that’s exactly what we’re seeing. The income gap continues to widen between the top 10 percent and the bottom 90 percent of American workers — in fact, the data shows that America’s income gap has been widening at an accelerating rate since 1970:

Capital disparity. Today, rates of return on privately owned capital can exceed a person’s earned income by 400 percent or more. This means Americans in the top tax bracket can add to their wealth simply by owning wealth at a much faster rate than low-wage Americans can save money by working a full-time job. As mentioned above, the rate of return on privately owned capital has been increasing since the 1950s, and economists project that it will skyrocket over the coming decades:

Purchasing power. Between 1988 and 2023, median usual weekly real earnings for full-time wage and salary workers aged 16 and over increased slightly from $329 (in 1982-84 CPI adjusted dollars) to $363. In other words, real wages have continued to remain relatively stagnant for most Americans.

Personal debt. As of 2023, Americans’ credit card debt has hit an all-time record of $1 trillion. Americans also own $1.77 trillion in student loan debt, due to decreased federal spending on student loans. This debt is making it even harder for Americans to earn and save enough to make it into the upper tax brackets.

Mortgage lending. Deregulation of lending enabled financial institutions to provide loans to individuals with poor credit histories or insufficient income (subprime lending). Deregulation also facilitated the growth of securitization, where mortgages were bundled into securities and sold to investors, leading to the proliferation of risky and opaque financial products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). The combination of these factors led to a bubble in the housing market — and the bursting of that bubble triggered a wave of mortgage defaults, the collapse of major financial institutions, and $700 billion in bank bailouts from the U.S. Treasury.

National debt. As we approach the end of 2023, the U.S. national debt continues to creep upwards of $33 trillion.

Military spending. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) budget now exceeds $877 billion (12 percent of all federal spending and nearly half of discretionary spending), which is more than next 10 countries’ spending combined. One can hear Eisenhower spinning in his grave.

In short, Supply-Side Economics did not work. It failed to achieve the effects predicted — in fact, a 2020 study by economists David Hope and Julian Limberg analyzed data spanning 50 years from 18 countries, and found that tax cuts for top earners had no beneficial effect on real GDP per capita or employment, and only succeeded at increasing inequality and making the rich wealthier.

These findings are supported by a 2014 report by Standard & Poor’s (S&P), which found that just 18 U.S. companies controlled $535 billion in capital — a full third of all the wealth in the country. Meanwhile, recent research by Princeton University shows that the top 0.0002 percent of Americans (a total of just 735 people) hold as much wealth as the bottom 99.9 percent of Americans (331 million) combined.

The good news is that some signs point toward positive change. In 2023, the federal government spends $1.19 trillion (about 8 percent of its budget) on programs for people and families facing economic hardship. K-12 schools nationwide receive $85.3 billion total, or $1,730 per pupil, from the federal government.

But a lot’s going to have to change in order for the 99 percent to have a fair shot at the American Dream. At the very least, we’re going to have to recognize that’s it’s not Republicans or Democrats who are the enemy; not Christians or Muslims; not cops or weed smokers — it’s the folks at the top who’ve been the problem all along: the bosses; the 1-percenters who know they’re secure as long as we’re distracted fighting among ourselves for the scraps.

To wrap up, let’s quickly recap exactly what we mean when we say “late-stage capitalism.” We’re talking specifically about a form of capitalism characterized by:

Extreme income inequality. A significant gap exists between the wealthy elite and the rest of the population, leading to a concentration of wealth and power among a small number of individuals.

Dominance of corporations and the ultra-wealthy. Large corporations and multi-billionaires hold substantial influence over both the economy and political processes, to the detriment of smaller businesses and workers.

Erosion of worker rights. Labor protections and workers’ rights weaken, resulting in precarious employment and reduced bargaining power for laborers.

Consumerism and financialization. A culture of excessive consumption and materialism fuels cravings for the next hit of dopamine. For similar reasons, people engage in complex speculative trading, often using money borrowed on credit. Hence we get a…

Debt-based economy: The economy relies heavily on unsustainable levels of debt, both at the individual and national levels. Banks, corporations, workers, and even the federal government borrow more than they contribute to the economy — fueling a cycle of loan defaults, bailouts, and deepening debt.

I hope this post has been at least somewhat informative, and has helped clarify some of the semantics around late-stage capitalism — what we mean when we refer to it, what factors and policy decisions led to it, and what effects it’s had on working Americans, and on the country as a whole.

Over my next few posts, I’ll dive more deeply into some related issues that we didn’t really have time to explore here — specifically:

The erosion of labor rights in today’s gig economy (published!)

How our post-COVID economy has become increasingly characterized by speculative gold-rush trading in wildly volatile meme stocks and cryptocurrencies

How the “growth-hacking” mindset we’ve inherited from Silicon-Valley tech companies drives cycles of worker exploitation while producing very few goods that people actually need

How late-stage capitalism and growth-hacking reward unsustainable exploitation of natural resources, leading to the decimation of this beautiful planet we call home

How AI has disrupted many industries, including some venerable arts, creating a highly unstable job market in the immediate term without having yet solved any of the long-term problems it’s been created to help solve

Maybe we’ll dive into some other topics, too. Only way to find out is to hit that Subscribe button below. And if you found any of this useful or informative at all, you might consider buying me a cup of coffee to sip while I write the next one: paypal.me/writingben

Many thanks. I have been studying Richard Wolff and he has not mentioned late stage capitalism but I imagine he might agree. I know nothing of Ernest Mandel who coined the term in a graduate thesis. I did love Marcuse who accepted the term. This seems very lucid. I am 75, two doctorates and a low income widow. At one time I helped several, 2k, seriously Ill folks, as an epigeneticist aka natural health and life balance. I wish I could support you. I just got my SS check after the Friday night massacre. We must get rid of them and in my view capitalism. I'm here and also on Medium where I found you. Many thanks.

I'm not interested in this. I have my own work. That was then this is now. Men expect female support. I enjoy my freedom.